- Home

- Wayne Allen Sallee

The Holy Terror Page 14

The Holy Terror Read online

Page 14

Until the pain started in his hand, delayed and intense as if it had been submerged in scalding water.

He opened his mouth as if to scream. Haid clamped his own hand over Bastoni’s lower jaw and his fingers melted into his cheekbone.

He took his hand away to grab the empty bottle of Canadian Chub, which was ready to shatter on the floor. Bastoni’s face was as white as his eyes.

Down the platform, Danny O’Keefe was telling the commuters that Good Time Charlie had the blues:

“Everybody’s gone away, said they’re movin’ to L.A. There’s not a soul I know around. Everybody’s leavin’ town.”

Someone belched like the song was telling a tale that needed to be repeated.

Thirty seconds into the healing and no one saw anything. Maybe it was the song, maybe just plain old common sense. A Chicago State of Mind, patent pending.

“Nyk.” Bastoni said, before a piece of his tongue, like dried clay, fell from his mouth onto his lap.

Then he blinked and his hands started moving to undo the brakes on his chair. The left one functioned, the right one, the one he had grabbed with, flopped like a fish off Foster Avenue when the water pollution was just right.

Haid latched on to both his shoulders and pushed Bastoni back in his chair, back against the wall. He saw his radial tendons, sticking out, his knuckles white knots.

Bastoni’s body was shaking silently, blurring Haid’s vision. The crippled man made a gargling noise as his eyes swelled up and the whites turned into a snot-green jelly. His face was completely dry and there Haid was, sweating up a storm in his Australian suede jacket.

The skin under Bastoni’s lids cracked, the thin veins turning a light blue. Smoke came out of his mouth.

“In the name of the Father,” Haid said, and then someone turned up the music.

* * *

The first bass patterns of the song curled around the two men like the misty mother fog of a forgotten poet reverberating against the pissy tiles and the dank walkways, echoing off into infinity. Or at least the Clark/Lake Transfer platform.

Then the matching drumbeat, like a spoon spaded underneath an eyeball. Digging, digging...

“When I die and they lay me to rest...”

Haid felt the advantage of Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit In The Sky,” and worked with it, like the chicks did at the Lehmenn Court club where Vice Janssen used to watch their storefront aerobics. The slits doing their little pussy thrusts to Springsteen’s “Pink Cadillac.”

“Gonna go to the place that’s the best...”

Bastoni had to be dead. But he could still pray for his soul. “Who art in Heaven,” he continued.

“When I lay me down to die, goin’ up to that spirit in the sky...”

Jagged lines of cracked flesh erupted across Bastoni’s face.

“Please Father,” Haid whispered.

A disagreement ensued between two men getting off the northbound ‘A’ train. “Mahfuh piss mah cuff allays say, he say smoke my dick right here, man.” An elderly voice standing up for his rights, good for him.

And Bastoni wasn’t going into him. But he couldn’t let go. The dead man’s rib cage broke. The rest of Bastoni’s face dried up like Play-Doh left out in the sun, the departing train drowned out the song, the gashes got deeper and redder then blacker, and Lex Bastoni exploded.

Organs bursting within the corpse, grue welled out and slopped onto the wall, little bits of hair like nosehairs in a juicy looger you’d been working at getting all week. Heads turned then and saw Bastoni’s form collapse in on itself, saw bit of Lex on Haid’s chin, saw the Painkiller simply freak.

The “explosion” had hurt his head worse than before. He wasn’t the only one spooked by the destruction. People screamed and scratched their heads. First the guy is cutting up cripples and maybe blowtorching them in their chairs, now he’s blowing them up. Well, it’s a good thing the fucker got a taste of his own medicine.

A yell bellowing out of him, to shock himself into motion as much as those around him, he flung the chair with Bastoni’s remains in front of the oncoming southbound train. The conductor shielded his eyes as if a different type of crime was being committed.

Haid ran screaming past faces more there and there over there the trains palms pressed smelling oil perfume Chantilly maybe the lake wind newsprint.

Running drying blood screaming knocking over someone anyone train doors hissing open running crying weeping staring up to God and seeing only the State Street grid vents.

Francis Madsen Haid ran screaming up the stairs and through the turnstile and down the alleyway the city council had designated Marble Place.

Falling face down and skidding on the ice, standing, breath steaming. Stopping alongside a forest-green dumpster, it’s insides as hollow and enticing as a Venus flytrap, falling again to his knees. Waist bent, panting and puking like some kind of novice werewolf.

Chapter Twenty Eight

* * *

Jackson Daves stopped typing in the middle of the word dismemberment. The very word sickened him. How could such a coward be so violent? The Painkiller had to be a coward to be going after handicapped street people. There had been no other reports from the public sector on this sort of thing occurring, no perfectly healthy John Does being found, men who might have at least a fighting chance with the serial killer.

In 1946, William Heirens left the city dumbstruck when he cut six-year old Suzanne Degnan into pieces in a basement on Kenmore Avenue. Earlier that spring, the killer had been denied parole for the twenty-eighth time.

The “Painkiller”—and oh how he wished that that prim and proper blond newswoman hadn’t jumped at his idiotic wordplay, and just what the hell was he saying things like that to the camera anyways?—was as much a coward as the University of Chicago student living out his life at the minimum-security prison farm in Verona. How the hell was a cripple in a wheelchair supposed to defend himself? Why direct such anger at them?

This was why Daves had stopped typing his two-fingered pavane. His chair creaked as he leaned back, sighing. The sigh turned into a shiver, as it did during similar times that were thankfully few and far in between.

The detective blinked and wiped the corner of his eye with the tip of his little finger’s nail. His cuticles were not well-manicured, not by any means. But neither were they dirty; Daves used the multi-colored plastic toothpicks from Geena Reno’s on Wellington, a bar that served deli sandwiches tented in plastic wrap, to scrape out the dirt and ink several times a day. This, and his constant rechecking to see if his fly was open, these two things were the detective’s obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

Aside from trying to find a serial killer.

Across the green and black tiled floor, Detective Petitt was conversing with a beat cop name of Lieder, one hand splayed against the beige wall opposite the varnished wood door with 19th District imprinted in black on the pebbled glass. Leider was scratching his sootcolored moustache. Behind him, next to a four drawer black filing cabinet, was a poster for the Ten Most Wanted In Chicago. This was for criminals with faces and names, like Eddie Weems, who gunned down three Latin King in September, not unknowns. And so it was that the Painkiller only received an honorable mention near the bottom of the sheet. That last was Dave's term.

Daves spun his chair to look at the Phantom of The Opera framed print, not the one for the current Andrew Lloyd Weber production but rather an irresolute, utterly despondent study in brown and tan and green by young turk Douglas C. Klauba. The print was suspended next to the file cabinet near his own sectioned off area of the "bull pen." In this city, if you couldn't write or draw worth a bronzed bladder, but were still chilled by the ghastly beauty of it all, then you became a cop. He wondered for a moment if that was what brought Ileana Cantu over to the Academy. Seeing the city the way an artist like Klauba did. Daves had been secretly pining for the Chicago District detective in training for weeks.

He looked back down at his notes next to th

e manual Smith-Corona Corsair Deluxe. At the crap that didn't make sense. He'd talked to Bervid over at County, and got the composition of the remains of Dolezal, the Jerrickson woman, and the John Doe in the subway.

It had taken several minutes for Bervid to spell out everything to him:

What it amounted to was…well, he'd been expecting the more gruesome hydrochloric or sulfuric aice, something along those lines. Instead, what it all amounted to was, the breakdown consisted of mostly inactive ingredients in Ben Gay or Chiropractic Mineral Ice. A call to Pfizer Inc., on East 42nd in Manhattan, verified the former.

What the hell was the killer using? His work was of the precision of, shit, of Jack the Ripper or Ed Gein.

Christ. Therapeutic balm.

Jesus Christ.

Chapter Twenly-Nine

That same Christmas Eve, while the American Dream was listening to the embellished details of the events in the State Street subway, Vic Tremble and Reve Towne were busy checking out a piece of information that might ID Grandma’s killer.

While doing a bit of post-Thanksgiving cleaning, Colin Nutman had come across a book that the sidewalk preacher had brought in the night of the Surf City party. The night of Grandma’s murder. He showed it to Mike Surfer, still wheeling around in a dejected funk, and he halfheartedly suggested Nutman give it to Reve or Evan. Tremulis had sauntered through the doors of The Mardinn as Reve was thumbing the copyright page of Frank Haid’s psalm book.

Inwardly ecstatic that the girl was in the lobby, Tremulis imagined that Reve had Tourette’s Syndrome, her body twitching to a hideous beat. “Vic Tremble,” she said as he walked over. “How are you? Merry Christmas early.” She showed him the book and about where it had come from.

“Think the killer dropped it?” He asked and Reve shrugged her shoulders. “Mike see it?”

“Yup,” Reve said, still scanning the pages, her hair brushing her fingertips. “Said it wasn’t Grandma’s.”

She handed the book over to him when he asked for it. Tremulis was so into his fantasy that he paused a moment to look at the black cover, trying desperately to find the bent ridge that a palsied grip would leave. He desperately wanted her to be crippled. All of his own books had the tell-tale ridges of someone having to grip a book tightly or not at all. Future historians would know of every book he’d read, from Nelson Algren to Chet Williamson.

“Psalms.” He said it just to say it.

“Grandma was a Roman Catholic, and this book was printed by the Franciscans...”

“So, if it was the killer’s, Reve—”

“Exactly.” She pointed a finger at Tremulis. “He murders the handicapped. Evan’s been talking about this guy being a wannabe savior...”

“Reve, this guy is butchering defenseless people!”

“Welcome to Chicago.” She scowled. “What kept you?”

“Okay, so it came out that way...” Tremulis bent his arms behind his back, each hand gripping the opposite elbow. Reve put a finger into her palm like a cigarette in an ashtray, only without twisting it.

“But their deaths themselves could have been painless,” she said. “What Evan means—”

“Reve, taking away someone’s pain, killing them painlessly, shit. They were defenseless. That’s it.” He liked to imagine that Reve was crippled because the fantasies showed her strength. To imagine her naked would be to make her vulnerable. Make her defenseless, in his mind’s eye.

“But he does have a pattern, weak as the connection is,” Reve said. “The wheelchairs. Maybe he’s doing what he thinks is best for everyone. It’s his disposal of the corpses that gives me the chills.”

“Reve, do you know how that sounds?”

“Yes I do, Vic.” Her hands blossomed away from her shirt. He noticed for the first time that the shirt depicted Omaha, The Cat Dancer. “That rag Phases on the north side is referring to the guy as another incarnation of the Tylenol killer. The guy who put cyanide in aspirin bottles, for chrissakes!”

“Hey, I know. Stop jumping on me,” Tremulis wanted to say something clever, like a character in a William Relling Jr. novel. Something along the lines of how he hated the Tylenol killer because, thanks to the unknown murderer from September of 1982, safety seals were being put on virtually everything he had to struggle to open on a daily basis.

“Vic, you know I’m not.” She touched his hand then and he knew he must find the Painkiller, wondering if it was Reve that filled Evan Shustak with the same insane forces.

“It’s not that,” he confessed. “I’ve... I’ve always had a kind of violent nature. Not like an angry drunk or a closet schizo, nothing like that.” He scratched his scalp, absently wondering if Reve could smell his body odor through his sweatshirt when he raised his arm.

“Like people I’ve worked with over the years, my own family, they all pontificate that I have the most violent thoughts, and yet they’re the ones that keep the Rambo sequels coming. They eat that shit up with a spoon.” He gulped as his mouth dried up, something else he and Mike Surfer had in common.

“Or, here’s a good one, Reve!” No stopping him now that he was on a roll. “That doctor down in Decatur or wherever. Found out his son had Downs syndrome, remember?” Reve nodded. “Threw the baby to the ground so his skull shattered. Right there where the other babies were. Society lets him off, the jury found him not guilty because of sanity. My mother and my sister thinks that’s understandable. And yet my father says I talk like I have a candy asshole if I say I want to strangle a stupid stock boy at the Hard Rock Cafe.”

Reve’s gaze had softened, not hardened, as he had expected.

“Will society approve of the Painkiller?” Tremulis let his silence answer for him. They both looked over the book again, as if it was the killer’s diary.

There was a book mark—a receipt, actually—on the page marked with the Act of Contrition. ”I went to a Catholic school for a few years,” Reve said. “We ended each Friday’s class with an Act of Contrition.” The receipt, faded from the moment it was birthed from the register, simply rang up the price and the sales tax. The book cost two dollars and ninety-five cents. Tremulis continued flipping through the pages.

One page was dog-eared, bent back. The page held part of a psalm, the facing page was an illustration of St. Vitus, a child martyr.

“Waitasec,” Reve said suddenly. “This receipt looks like it came from St. Sixtus.”

“Over on Madison? I’ve been there, that’s where I met Mike, in fact.”

“Ever see that crazy lady in the bonnet?”

“Yea, she’s a trip.”

“I bought Mike a book from there once,” Reve said. “Trumpets of Beaten Metal. Said how the title reminded him of wheelchairs. That’s how I recognize the receipt.” She brushed her hair back.

Tremulis wished his family could be half as proud of his disease, even if it didn’t have a pretty label, as Mike Surfer was of his. The man made him think that the Givers of Pain and Rapture had given him, Tremulis, the opportunity to be in chronic pain for most of his adult life. Maybe all of it; he truly couldn’t remember when it had ever been any better.

He looked at Reve, then at the book.

“What are we waiting for? Let’s go.”

* * *

They walked south through the alley behind the Title and Trust building, old newspapers and McDonald’s cartons flattened to the ground in original patterns by dried vomit and urine from nights past. Tremulis showed Reve the breezeway on the west side of the church where all the motorcycles were parked, and was pleasantly surprised that she had never noticed. It was an oddity, conjuring images of all these Franciscan monks on their choppers, cassocks flying in the wind.

He had asked a suit on the corner, once the guy had a helmet slung over the shoulder of his three-piece, what the deal was. The suit answered that he’d been parking his bike there for three years. Saying it like it made him something more than a nine-to-fiver behind a desk.

The chain-smoking woman wa

s gone from her perch at the doorstep of St. Sixtus. It was the first time both he and Reve had not seen her roosted there, slapping cigarettes—Reve thought that they were Lucky Strikes—into her mouth and judgments out of said mouth; blowing out smoke and indecipherable phrases at passerby. The cold weather had never kept her away before. Both were thinking that maybe the Painkiller was branching out in his quest for victims.

The gift shop of the church stood just to the left of the holy water receptacle in the lobby—a fountain where parishioners could fill up their plastic bottles—and one of the first things Tremulis noted was that Reve didn’t stop to dab holy water on herself as they entered. He dipped his hand into the dish by rote, but did not touch his forehead. Rather, he touched his first two fingers to his neck, as a woman might her perfume, because that was where Tremulis’s muscles were tightest, where his spasms were unrelenting.

Just before the gift shop, a beige statue of St. Sixtus faced the two of them, sagely flashing a peace sign. A young Mexican boy stood behind the waist high glass counter. He was reading a copy of Catholic Monthly, and was wearing a black turtleneck sweater. A silver medal depicting S. Lazaro, patràn de lospobres, dangled just below his collarbone.

Reve walked up to him and pulled the psalm book from the back pocket of her Gitano jeans as smooth as a dealer putting up front money. Book in one hand, receipt in the other, Reve kept it simple: ”Hi. These from here?”

The Mexican boy didn’t know what to make of it, maybe the pastor was sending someone by to see if he knew his stuff on the job. And he did, all right.

“Heck, yes, lady,” he said in that humble way most Mexicans or Ricans in Chicago have when speaking English. “If you’d like, I’d be happy to point out several other such books off you might find of interest.” He beamed as only young boys or girls on their first jobs did.

“No, that’s all right,” Reve said. Tremulis was fingering a scapula blessed by Pope John Paul II on display, then turned away. They both thanked him.

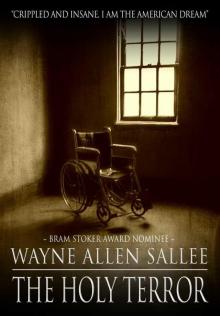

The Holy Terror

The Holy Terror